IBash Notebook

Feb 19, 2015 • 18 min read.

Did you know that there’s a Bash kernel for Jupyter Notebook? It even

displays inline images. To give you a glimpse, the code cell below makes

an API call to memegenerator.net, which

generates images on demand. From the response, the URL of the generated

image is extracted using jq and subsequently downloaded using curl.

The output is then displayed as an inline image by piping it to a

function called display. Perhaps a bit contrived, but if not with a

meme, how else am I supposed to grab your attention these days?

In this post, I first give some background on notebooks and the IPython Notebook/Jupyter project. Then, I explore the idea whether this “IBash Notebook” has the potential to become a convenient environment for doing data science. Subsequently, I explain how I added support for displaying inline images. As an aside, I wonder whether it would be feasible and worthwhile to publish my book Data Science at the Command Line as a collection of notebooks. Finally, I discuss which issues remain to be improved and how you can try out IBash Notebook for yourself. I’m curious to hear what you think.

You get a notebook. And you get a notebook. Everybody gets a notebook!

Let’s take a step back for a moment. Doing research is hard. Recalling which steps you’ve taken, and why, is even harder. To be an effective researcher, you may want to keep a laboratory notebook. Besides having a record of your steps and results, this also allows you to improve reproducibility, share your research with others, and, yes, think more clearly. So, why wouldn’t you keep a notebook?

Well, if you perform your research or analysis on a computer, where most steps boil down to running code, invoking commands, and clicking buttons, keeping an analogue notebook is rather cumbersome. Fortunately, since recently, digital counterparts are quickly gaining popularity. For the R community, for example, there’s R Markdown. And for those who use the Python scientific stack, there’s IPython Notebook. Both solutions are free and allow you to combine code, text, equations, and visualisations into a single document.

The people behind the IPython project saw the potential of having a language-agnostic architecture. By creating a flexible messaging protocol, writing good documentation for it, and rebranding the project as the Jupyter project, they opened the door to other languages. And now, languages like Julia, Ruby, and Haskell have their own kernel. Beaker, a completely different project, even supports multiple languages in the same notebook.

What about poor old Bash?

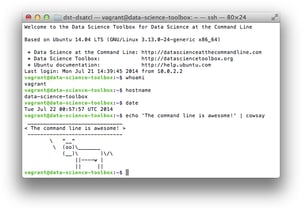

To demonstrate how easy it is to create a new kernel for IPython Notebook, Thomas Kluyver created a Python package called bash_kernel. This Bash kernel basically works by using pexpect to wrap around a Bash command line. When I stumbled upon this package I immediately got excited. This could be much more than just a demonstration. Call me crazy, but I believe that with some additional effort, we might have an IBash Notebook that would have some important advantages over a terminal (which is the standard environment to interact with the command line; see image below).

First, and perhaps most importantly, the command line is ad-hoc in nature, which makes it difficult to reproduce your steps or share them with your peers. To improve reproducibility, you could put those steps in a shell script, Makefile, or Drakefile, but when you’re working in a notebook, they would be stored automatically.

Second, if you’re running a server or virtual machine, there would be no

need to ssh into it. As a result, Microsoft Windows users wouldn’t

need to resort to a third-party tool like

PuTTY anymore. I’m

particularly interested in this advantage, together with the next two,

because ever since I started writing Data Science at the Command

Line, I’ve been looking for

ways to make the command line more accessible to newcomers.

Third, for users who are new to the command line, a notebook with code cells could be less intimidating than a terminal with a prompt. Because the browser (and perhaps also IPython Notebook) is a familiar environment, the threshold to try out the command line will be lower.

Fourth, in order to view an image located on a server or virtual

machine, you normally have to go trough an extra hoop. Approaches that I

know of are either: (1) copy this image to the host OS, (2) forward X11,

or (3) serve it using, say, python -m SimpleHTTPServer and then open

it in a browser. With a notebook, images can be shown inline. Which

brings us to…

Adding support for displaying inline images

For the Bash kernel to be a convenient environment for doing data science, it could use a few additional features besides running commands. Thanks to the architecture of IPython Notebook, inline Markdown and LaTeX equations work out of the box. Having seen Gate One (a browser-based terminal that I had running on 200 EC2 instances for my workshop at Strata NYC) and pigshell (a shell-like website that lets you interact with various APIs as Unix files), which are both able to display inline images, I knew that’s what the Bash kernel needed next.

I initially thought this would be as easy as detecting the MIME type of

the output of a command. That way, when you would run cat file.png, an

image would be shown automatically. Unfortunately this approach didn’t

work because, as I later learned, pexpect isn’t meant to transfer

binary data. With some suggestions from Thomas

Kluyver, I implemented the following

solution instead. (You may decide whether it’s a hack or not.)

The solution includes a Bash function called display that is

registered when the kernel starts. That way, images can now be displayed

by running something as simple as:

display < file.pngor something as involved as:

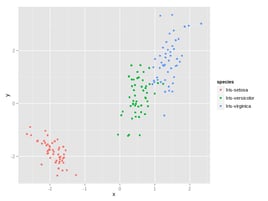

cat iris.csv | # Read our beloved Iris data set

cols -C species body tapkee -m pca | # Apply PCA using tapkee

header -r x,y,species | # Replace header of CSV

Rio-scatter x y species | display # Create scatter plot using ggplot2which produces:

In case you’re interested, cols and body are used to only pass

numerical columns and no header to tapkee,

which is a fantastic library for dimensionality reduction by Sergey

Lisitsyn. These two Bash scripts, together

with header and Rio-scatter, can be found in this

repository.

Speaking of command-line tools for plotting,

Bokeh, which is a Python visualization

library built on top of matplotlib, will soon have its own command-line

tool as well.

To see what the display function looks like, we can run type display

in a notebook:

display is a function

display ()

{

TMPFILE=$(mktemp ${TMPDIR-/tmp}/bash_kernel.XXXXXXXXXX);

cat > $TMPFILE;

echo "bash_kernel: saved image data to: $TMPFILE" 1>&2

}In words, display saves the standard input to a temporary file and

prints the filename to standard error. After a code cell has been

evaluated, the Bash kernel simply extracts the filename from the output,

detects its MIME type using the

imghdr library, and

sends the image data (encoded with base64) to the front end. Easy peasy.

I chose the name “display” because there’s also a command-line tool in ImageMagick called “display” that accepts image data from standard input and shows it in a new window. Because that tool works only when X is running, I figured that a function called “display” could serve as a drop-in replacement when using IPython Notebook.

Aside: Publishing a book as a collection of notebooks

IPython Notebook can also be used to write entire books. Mining the Social Web, Probabilistic Programming and Bayesian Methods for Hackers, and Python for Signal Processing are but a few examples of books that have been published as a collection of notebooks (usually one notebook per chapter). The main advantage of a notebook as opposed to a book is that you can immediately run the code yourself. Instead of passively reading about a certain package or tool, you can actively try it out.

I wonder if I could (and should) do the same with my book Data Science at the Command Line. As an initial test, I manually converted part of the first chapter to a notebook, which you can view on nbviewer. Converting the book’s source code wouldn’t be too difficult, especially if we to convert it to Markdown and use ipymd. What would be more challenging are packaging and distribution.

The book introduces over 80 command-line tools, and installing them manually would take the better part of a day. I do offer a virtual machine based on Vagrant and VirtualBox that has everything installed, but I suspect there’s a better way to package this with IBash Notebook. For example, recently, Thomas Wiecki created a Docker container that launches an IPython notebook server with the PyData stack installed. And the tmpnb project seems very promising as well. I must admit that I haven’t had time to look into Docker and these two projects at all.

Distribution is then something I would need to figure out with my publisher O’Reilly Media. Considering the recent efforts for the book Just Enough Math by Andew Odewahn, O’Reilly’s CTO, and their forward thinking regarding publishing in general, I foresee many opportunities.

What’s next?

Having inline Markdown, equations, and images sure is nice. However, in

my opinion, the Bash kernel currently has two issues that hamper

usability. First, the output is only printed when the command is

finished; there are no real-time updates. This is especially

inconvenient if you want to keep an eye on some long-running process

using, say, tail -f or htop. Second, there’s no interactivity with

the process possible. This means that you cannot drop into some other

REPL like julia or psql. If there’s sufficient interest in IBash

Notebook, then I suspect that these issues can be solved. Regardless, I

believe that despite these two issues, IBash Notebook could very well

serve as a means to introduce people to the command line.

If you want to try out the Bash kernel for yourself, you should install IPython 3 (which is currently in development). Then, you can clone the Bash kernel GitHub repository and install the package. (Best to do this all inside a virtual environment.) Next time you start a new notebook, you should be able to select the Bash kernel in the top-right corner.

So, what do you think? Do you agree that IBash Notebook has potential? Am I crazy thinking that the command line can ever live outside the terminal? Would you like to see my book published as a collection of IBash notebooks? So many questions. Let me know on Twitter.

— Jeroen

Thanks to Rob Doherty and Adam Johnson for reading drafts of this.

Would you like to receive an email whenever I have a new blog post, organize an event, or have an important announcement to make? Sign up to my newsletter: